“There is No word in the Torah that is vain: each letter teaches, and every silence also speaks”

Attributed to the sages of the school of Rabbi Yishmael (II century)

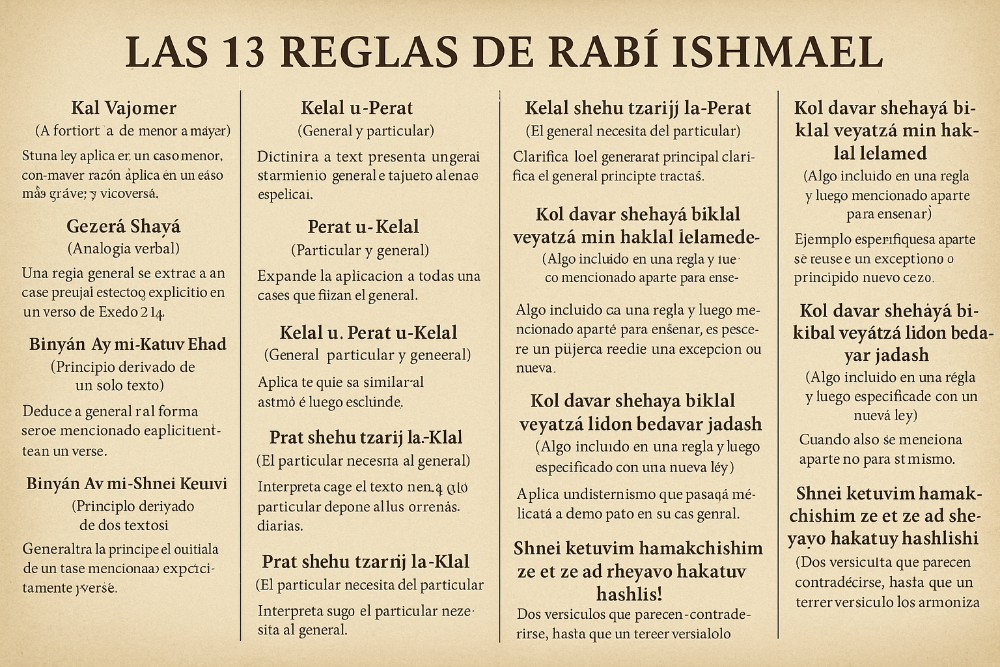

Rabbi Yishmael made these 13 rules to systematize the way in which wise men have interpreted the written Torah (the Pentateuch) in the light of the oral Torah. Its purpose was not to create new laws, but to extract the implications of legal and theological contained in the text, applying principles of logical reasoning, language and context.

These rules are recited traditionally at the beginning of morning prayer in judaism, before the section of the korbanot (sacrifices).

VIDEO IN SPANISH

The Thirteen Rules of Rabbi Ishmael — Explanation and Examples

1. Kal Vajomer (קל וחומר) — “A fortiori” or “lowest to highest”

Definition:

If a law applies in a smaller case, with greater reason applies in a more severe case, and vice versa.

Example:

If the Torah commands honoring parents (an obligation natural), how much more should be honoring to God, who is the Creator!

Another classic example:

“If the priests, who are forbidden to marry certain women, they may eat of the offerings, with greater reason, the common people, who do not have this prohibition, you can do so when you are allowed to.”

2. Gezerá Shavá (גזרה שווה) — “Analogy verbal”

Definition:

Comparing one passage with another that contains a word or expression identical, to transfer the laws or concepts from one context to another.

Example:

In the study of the Shabbat, the word “melajá” (work) appears both in Exodus 20:10 as in Exodus 35:2.

From this coincidence, the sages deduced what types of jobs were prohibited on Shabbat (the same ones involved in the construction of the Tabernacle).

VIDEO IN ENGLISH

3. Binyán Av mi-Katuv Eḥad (בנין אב מכתוב אחד) — “Principle derived from a single text,”

Definition:

A general rule is drawn from a particular case explicitly mentioned in a single verse.

Example:

If the Torah says that a person who steals must return what was stolen (Leviticus 6:4), this principle extends to all cases of misappropriation, even if not specifically mentioned.

4. Binyán Av mi-Shnei Ketuvim (בנין אב משני כתובים) — “Principle derived from two texts”

Definition:

If two verses different set to the same principle, be generalized as a rule applicable to all similar cases.

Example:

If both Exodus and Deuteronomy teaches that the animals must rest on Shabbat, it follows that every living being under human control should rest that day, even though it is not explicitly mentioned.

5. Kelal u-Pérat (כלל ופרט) — “General and particular”

Definition:

If a text presents first a general statement and then a specific one, the interpretation is limited to the particular.

Example:

Exodus 22:9:

“If someone gives his neighbor a donkey, or an ox, or a sheep, or any animal to keep...”

Here “any animal” (general) continues to specific examples; therefore, the rule is applied only domestic animalsnot all living beings.

6. Pérat u-Kelal (פרט וכלל) — “Particular and general”

Definition:

If you are first mentioned something specific, and then a general expression, we extend the application to all cases that fit the generalization.

Example:

Leviticus 19:9:

“When you harvest the harvest of your land, do not reap to the very last corner of your field...”

Here the Torah begins with a concrete example (field) and then he says “your land” (general), extending the obligation also to vineyards and orchards.

7. Kelal u-Pérat u-Kelal (כלל ופרט וכלל) — “General, particular and general”

Definition:

When a text combines the general, the particular, and then again, the law applies only thing that is similar to the particular case.

Example:

Deuteronomy 14:26 speaks of purchase “anything you want: cattle, sheep, wine, or liquor, or anything you ask”.

Here the rule states that the permission refers to food products, or holidaysnot to goods completely oblivious as weapons or tools.

8. Prat shehu tzarij the-Klal (פרט שהוא צריך לכלל) — “The particular needs of the general”

Definition:

When the particular text depends on the general to be understood, both are interpreted together.

Example:

If the Torah mentions “the sacrifice of the Shabbat” within “the daily offerings”, it is understood that the sabbath sacrifice is a special case of the daily sacrificenot something independent.

9. Kelal shehu tzarij the-Pérat (כלל, שהוא צריך לפרט) — “The general needs of the particular”

Definition:

The opposite of the previous one: the general principle is clarified, it is only thanks to the specification in particular.

Example:

When the Torah says “thou shalt offer sacrifice”, and then specify “lambs without defect”, the details define the scope of the general mandate.

10. Kol davar shehayá biklal veyatzá min haklal lelamed (כל דבר שהיה בכלל ויצא מן הכלל ללמד) — “Something included in a rule, and then mentioned apart to teach”

Definition:

If something is already included in a general category, is again referred to, separately, is to teach an exception or a new beginning.

Example:

The general command of “keep the Shabbat” includes rest, but when it specifically mentions “do not kindle a fire”, it is understood that this case serves to define the type of work forbidden, not to add a new precept.

11. Kol davar shehayá biklal veyatzá lidon bedavar jadash (כל דבר שהיה בכלל ויצא לידון בדבר חדש) — “Something included in a rule, and then specified with a new law”

Definition:

If a particular case out of the general framework and applies a different standard, you can't go back on the general.

Example:

The sacrifices generally offered on the altar, but the sacrifice of the Passover has its own laws (should be eaten on a family, on a specific night), so that do not apply the general rules of other sacrifices.

12. Kol davar shehayá biklal veyatzá lelamed what lelamed al atzmo yatzá (כל דבר שהיה בכלל ויצא ללמד לא ללמד על עצמו יצא אלא ללמד על הכלל כולו יצא)

Definition:

When something is mentioned apart not for himself, but to teach a rule applicable to all general category.

Example:

If the Torah specifies a punishment for a crime included in a broader category, the purpose is to to illustrate the general principle that governs all that class of cases.

13. Shnei ketuvim hamakchishim ze et ze ad sheyavó hakatuv hashlishi (שני כתובים המכחישים זה את זה עד שיבוא הכתוב השלישי ויכריע ביניהם) —

“Two verses that seem to contradict each other, until a third verse the harmony”

Definition:

When two texts seem to be in opposition, is looking for a third passage that reconciles, showing the context or condition of each one.

Example:

Exodus 19:20 says, “God came down upon mount Sinai”, while Deuteronomy 4:36 says that “God spoke from heaven”.

A third verse makes it clear: “From heaven he made thee to hear his voice, and upon earth he shewed thee his fire” (Deut. 4:36), revealing that both assertions are complementary, not contradictory.

Conclusion

The 13 Middot of Rabbi Yishmael they represent the heart of the hermeneutical method rabbinical, where logic, grammar, and the reverence for the sacred text are combined to extract life principles, morality and law.

Each rule acts as a instrument of legal reasoning and spiritualby establishing a bridge between the written word and its oral interpretation.